Ramblings on metrical psalters, Ulster, and metrical doxologies

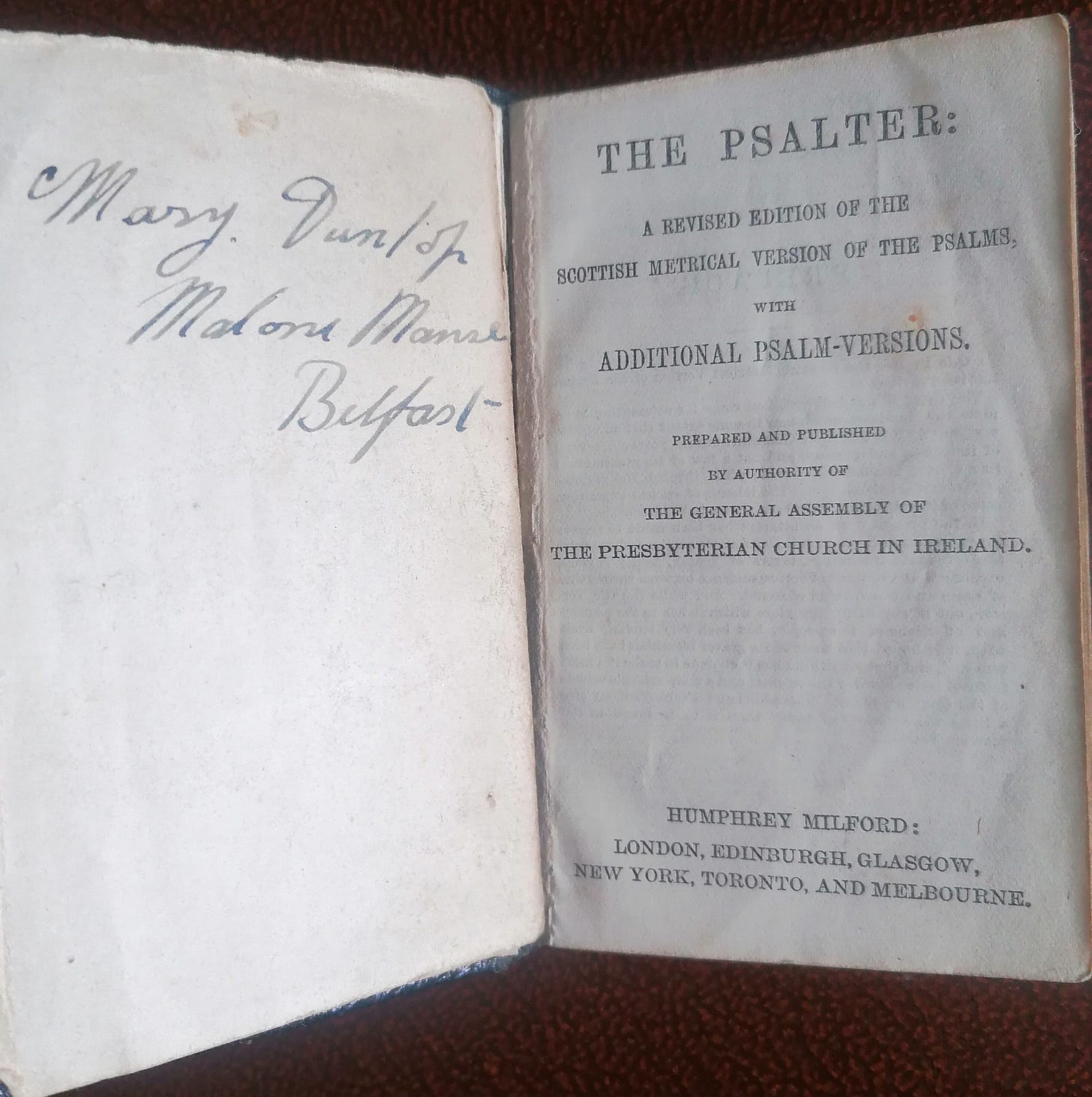

One of my prized possessions is the metrical psalter belonging to Mary Dunlop, my great-great-great-aunt. She moved from Scotland to County Antrim, Ireland, with her nieces, and was a Presbyterian, then the majority denomination of both Scotland and Ulster. Passed to me by my great-grandmother (still living, aged 90) this tiny psalter serves as a reminder of my direct Scottish Presbyterian heritage, and my wider descent from Ulster-Scots Presbyterians, as well as the vital importance of the metrical psalms to the worship of my predecessors and Ulster herself for the past 400 years.

Metrical psalms and psalm translation

The psalms are of a timeless depth and spiritual comfort. From using the Book of Common Prayer as my daily office and frame for my prayer life, this engagement with the Psalms has been through the setting of the Coverdale translation. Myles Coverdale’s seniority to the King James Version is shown throughout his translation, possessing the same timeless, reverent quality which early modern English has come to possess in modern times; but the incorporation of the mid-verse caesura — giving it the basic structure required for chant and half-verse responsorial — gives the psalms a deeply rhythmic flow which you don’t get from the prosaic rendering of standard Bible translations. The invitation to chant make the psalms feel so much more like poems, like hymns; and the acceptance of that invitation, to pay steady attention to the lyrics as they’re sung with your own voice, is deeply rewarding; moreover, singing the psalms connects us with the entirety of church tradition, and back into old covenant Israel.

The metrical psalms provide a beautiful alternative to the plainchant setting, and mostly set the psalms to the simplistic popular hymn form of common metre — being ABAB rhymed stanzas in an 8686 metre, typically iambic. ‘Amazing Grace’ uses this metre, for example:

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me

I once was lost, but now I'm found

Was blind, but now I see

Here are the first three verses of Psalm 137 in this style, from the 1650 Scottish psalter —

By Babel’s streams we sat and wept,

when Zion we thought on.

In midst thereof we hanged our harps

the willow-trees upon.For there a song required they,

who did us captive bring:

Our spoilers called for mirth, and said,

A song of Zion sing.

The Coverdale psalms, on the other hand, do not follow poetic metre [the asterisk represents the caesura, where the second line of the melody begins in a chant, or where the congregation will respond]:

By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept,* when we remembered thee, O Sion.

As for our harps, we hanged them up* upon the trees that are therein.

For they that led us away captive required of us then a song, and melody in our heaviness* Sing us one of the songs of Sion.

Undoubtedly, the 1650 translators drew from Coverdale’s versions. While both are beautiful, the reading of both styles at length evoke different moods, and the contractions which the metrical psalms must make can both remove depth and add pithiness at once.

To many, the devotional reading of biblical poetry in a form recognisable to modern English readers as poetic, puts one in the right mindset for approaching the text as more than prose. Even the rendering of the Coverdale psalms with line breaks — now common in modern versions of the BCP — achieves this effect to some degree;

By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept,

when we remembered thee, O Sion.

As for our harps, we hanged them up

upon the trees that are therein.

For they that led us away captive required of us then a song, and melody in our heaviness

Sing us one of the songs of Sion.

But they are still missing some of the natural musicality that comes with common metre.

To draw from my own testimony; when I would read the psalms devotionally from my KJV I would struggle to derive the full sense or meaning of a psalm, despite understanding them on a surface level. While this was likely also an issue of faith and a lack of truly meditative engagement, I believe it was also partly because of the lack of prompted engagement with them as poetry on the visual, linguistic, and musical level.

Evidently, metrical settings of the psalms for private reading have been successful historically, as seen in the efforts of Sir Philip Sidney and his sister Mary Sidney’s Sidney Psalter. Mary Sidney translated Psalm 137 with much creative freedom, thus:

Nigh seated where the river flowes,

That watreth Babells thanckfull plaine,

Which then our teares in pearled rowes

Did help to water with their raine,

The thought of Sion bred such woes,

That though our harpes we did retaine,

Yet uselesse and untouched there

On willowes only hang'd they were.Now while our harpes were hanged soe,

The men whose captives then we lay

Did on our griefs insulting goe,

And more to grieve us, thus did say:

You that of musique make such show,

Come sing us now a Sion lay. [...]

Despite the extent of creative interpretation, the iambic tetrameter rendering gives them an undeniable musicality which aids in the reading of the psalms as biblical poetry.

In modern times there is a general precedence for the poetic sections of the bible to be given line breaks, imposing a certain poesy even without linguistic or metrical effort to set them as such. The New King James Version renders Psalm 137 with little difference to the original KJV but with the addition of line breaks:

BY the rivers of Babylon,

There we sat down, yea, we wept

When we remembered Zion.

We hung our harps

Upon the willows in the midst of it.

For there those who carried us away captive asked us for a song.

And those who plundered us requested mirth,

Saying, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

A wider use of the metrical psalms for private psalm-reading — with appropriate knowledge of where they compromise on content compared to a formal biblical translation — could be very spiritually edifying for many, and bring to its full extent the taste for biblical poetry to be line-broken among readers and translators.

Musically, the metrical psalms have historically proven more accessible to the average Christian worshipper. They have become a cornerstone of Scottish Christian worship and global Presbyterian worship. The Covenanters — also known as Reformed Presbyterians — restrict their worship to the singing of metrical psalms only, without any musical accompaniment, which they justify with the hermeneutic of the ‘regulative principle of worship’ — that all facets of worship must be derived from scripture alone. Their form as musical lyric, instead of the often personal single-penmanship feel of the psalms, more easily lets them be absorbed in a congregational setting.

The Ulster Context, and a proposal

Now, to speak from an Anglican perspective — in my Irish context, the Church of Ireland — the musical use of psalms seems to be on something of a decline. Plainchant singing of psalms and canticles appears more difficult for congregations who are accustomed to the more common historic low church form of Anglican worship which has taken hold in the evangelical-forward Ulster. Despite plainchant being a beautiful historic form which we have brought down from the medieval church through the Reformation, it should not be idolised over the democratisation of communal worship (whilst retaining traditional beauty and reverence) which the Reformation sought. Indeed, even the High Church wing of the Church of England in the early 19th century maintained that the metrical psalms were a godly and accessible alternative to the shift towards hymnody that was occurring in the Low Church wing.1 While the use of responsorial psalmody remains in the Church of Ireland, with the narrowing of the lectionary prescription to one psalm each Sunday, and often only a single section of the psalm spoken, I suspect there is a lack of engagement with the psalms in Anglican congregations. Meanwhile the 1662 psaltery prescribes as many as 10 for the calendar day, depending on the length of the psalms.

The psalms are something to be wrestled with and absorbed, fraught with pain and suffering as much as with praise and adoration of God. They were the fundamental prayerbook and songbook of the early church; the cornerstone of monastic life; Martin Luther spoke of them as a little Bible within the Bible; and C.S. Lewis defended them in the light of confusion and accusations of contradiction in the mid-20th century. They must be a cornerstone of our devotional reading and prayer!

A reintroduction of the metrical psalms could be a remedy to this decline in appreciation, in both congregational worship, in smaller prayer groups, and in households. Their 8686 common metre give room for a lack of musical training, and can be easily sang to well known hymn tunes like ‘Amazing Grace’ and ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’. In the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster there remains a high view of the metrical psalms, which occupy a large portion of their hymnbook, with congregants often knowing the psalm tones from memory, and services generally including one psalm out of the 4-5 hymns sung. Perhaps we should look to the Presbyterians, Covenanters, and Free Presbyterians, and reclaim the metrical psalms as a common worship tradition, and as an element of Ulster Scots identity in the north. We see that the Eastern Orthodox Church in America is attempting to connect with the cultural and ethnic roots of their congregants through the adaptation of musical traditions like Appalachian Chant. Perhaps a return to regional historic music styles is a more fruitful way of bridging the widening gap between church worship and alienated laity; and in the Northern Irish context, shift self-identity away from politics and religious nominalism toward a more constructive, deeper, understanding of the past. The reclaiming of worship traditions continued by our Scottish Presbyterian predecessors, and refolding them back into Anglican practice, and throughout other denominations, is a way to reunite Christian worship with regional identity and life. Across the pond in America, the reintroduction of the Scottish metrical tradition into Anglican (and even Orthodox) worship could be a possible step in connecting with the ethnic roots in Ireland, Scotland, and Ulster specifically, which so many Americans treasure.

Metrical psalmody provides a style which is deeply rooted in Gaelic culture and in church tradition; elevated while simple; agreeable to church tradition; modular and accessible to musically untrained laity.

Metrical doxologies

To more appropriately adapt the metrical psalms to a liturgical context, it would be appropriate to add the Gloria Patri doxology to the end of each psalm. This, too, has been a part of Presbyterian tradition, and various translations have been written. The earliest Reformed psalters included doxologies, but ‘their place was diminished in the 1635 Scottish Psalter’, likely due to the influence of Puritanism; by the mid 20th century the Church of Scotland began singing the Gloria Patri doxology at the end of psalms during General Assemblies, and this was adapted by other parishes.2 The adaption they used is graceful:

To Father, Son, and Holy Ghost,

the God whom we adore,

Be glory, as it was, and is,

and shall be evermore.

Amen.

Another historic version goes:

All Glory to the Father, Son

and Spirit, One and Three:

As was, and is, and shall be so

through all eternity.

Amen.

And John Milton translated the Gloria (in 8787 metre) as

To Father, Son and Holy Ghost,

immortal glory be;

As was, is now, and shall be still

to all eternity.

Amen.

I have also written a metrical version, making use of a slant rhyme on the B rhyme:

All glory to the Father, Son,

And to the Holy Ghost:

As it shall be ‘till days are done,

And has been, all days passed.

Amen.

Conclusion

While my thoughts here have been somewhat scattered, I believe they sufficiently show my concerns, and hope that a wider reappreciation of the metrical psalms outside of the Presbyterian context, and outside of their use for communal worship alone, could be greatly edifying to the church.

https://laudablepractice.blogspot.com/2020/09/said-or-sung-old-high-church-defence-of.html

https://www.churchservicesociety.org/sites/default/files/journals/1962-44-45.pdf